Historic Manassas Virginia

Manassas was a collection of plantations before the opening shots of the First Battle of Bull (Manassas). Union Brigadier General Irvin McDowell commanded 35,000 troops of the Army of Northeastern Virginia who marched from Washington, D. C. to Centreville along the Alexandria Turnpike to seize Manassas Junction. This was a vital transportation route where the Orange and Alexandria Railroad met the Manassas Gap Railroad leading west to the Shenandoah Valley. If McDowell seized this junction, he would control the best overland approach to the Confederate capital of Richmond. The fate of Manassas was forever changed.

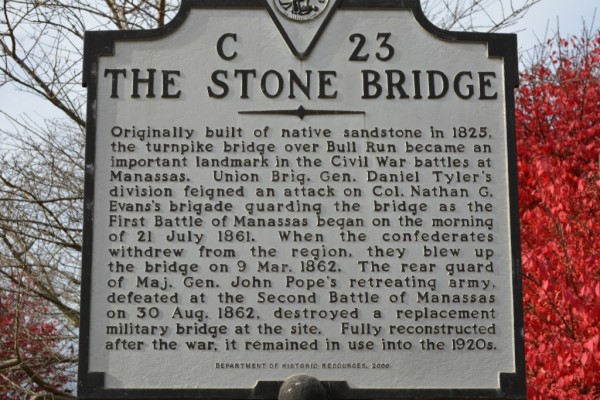

The Union attack on July 21, 1861 at Sudley Springs was originally planned to cross Bull Run at the Stone Bridge. But false rumors lead Union planners to believe the Stone Bridge was readied with explosives for the Union approach. As a result, the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, the nucleus of the Army of Potomac, moved north to cross Bull Run and attacked the Confederate Army of the Potomac under the command of General P. T. Beauregard. The Union attack swept south across the Warrenton Turnpike and pressed forward to Henry Hill. There the Union attack ran into Virginia’s First Brigade (later known as the Stonewall Brigade). General Thomas Jonathan Jackson stood tall on Henry Hill and with the help of the Third Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah under General Barnard Elliot Bee of South Carolina, the Union assault turned into a retreat. The Union Army fled east using the Stone Bridge to cross Bull Run and use the Warrenton Turnpike to flee to Centreville, consolidate, and return to Washington.

The original Stone Bridge (c. 1825) remained intact through 1861. On the 9th of March 1862 General Joseph E. Johnston and the Confederate Army of the Potomac left winter camp in Centreville and Manassas. After securing supplies at Manassas Junction, the army rear guard used explosives to destroy the Stone Bridge after anticipating a march south to defend Union advances on Richmond.

Union Army engineers eventually constructed a temporary wooden span across Bull Run using the remaining bridge abutments. This bridge served Union General John Pope’s army at Second Manassas, August 28-30, 1862. After suffering another costly defeat, Union forces used the Warrenton Turnpike bridge as their primary line of retreat. In the early hours of August 31, the bridge was again destroyed, this time by the Union rear guard.

This Virginia Department of Historic Resources interpretive highway marker (c. 2000) is on Lee Highway/Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike (Route 29) on the edge of Manassas National Battlefield Park in Centreville (Fairfax County). The marker reads:

“Originally built of native sandstone in 1825, the turnpike bridge over Bull Run became an important landmark in the Civil War battles at Manassas. Union Brigadier General Daniel Tyler’s division feigned an attack on Colonel Nathan G. Evan’s brigade guarding the bridge as the First Battle of Manassas began on the morning of 21 July 1861. When the Confederates withdrew from the region, they blew up the bridge on 9 March 1862. The rear guard of Major General John Pope’s retreating army, defeated at the Second Battle of Manassas on 30 August 1862, destroyed a replacement military bridge at the site. Fully reconstructed after the war, it remained in use into the 1920’s.”

This is my overall accounting of both Civil War battles fought between Groveton and Bull Run:

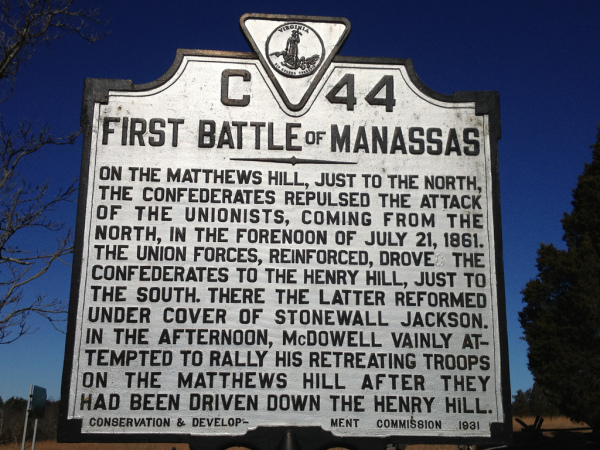

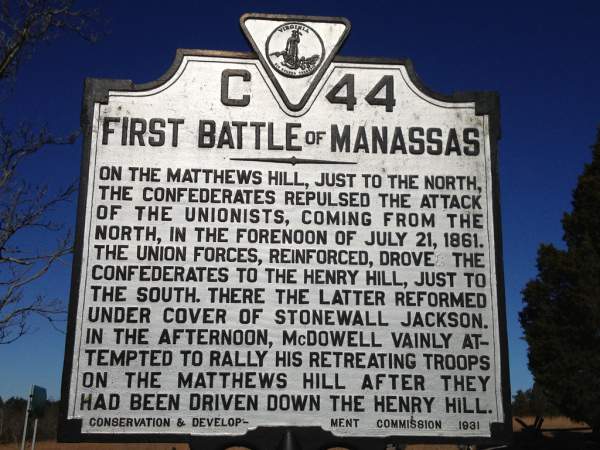

This 1931 Virginia Conservation & Development Commission historical highway marker is on Manassas National Battlefield Park near the Robinson House on Lee Highway (Route 29) between the Stone House at Sudley Road (Route 234) and Stone Bridge at Bull Run. The marker reads:

“On the Matthews Hill, just to the north, the Confederates repulsed the attack of the Unionists, coming from the north, in the forenoon of July, 21, 1861. The Union forces, reinforced, drove the Confederates to the Henry Hill, just to the south. There the latter reformed under cover of Stonewall Jackson. In the afternoon, McDowell vainly attempted to rally his retreating troops on the Matthews Hill after they had been driven down the Henry Hill.”

The Manassas National Battlefield Park like the City of Fredericksburg experienced two major battles during the Civil War. The first battle of the Civil War came as Lincoln ordered Union General Irvin McDowell to lead 35,000 troops out of Washington, D.C. to seize the railroad junction at Manassas which connected the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, and the Manassas Gap Railroad which led to the Shenandoah Valley. If General McDowell’s Army of the Potomac could capture Manassas Junction the Confederate forces would be divided and movement of troops and supplies would be disabled between Richmond and Washington. But Confederate General P. T. Beauregard Commander of the Confederate Army of the Potomac was waiting for the Union attack at Bull Run.

On July 21, 1861 a series of movements at Bull Run by Union forces signaled the start of the battle. Previous to this movement General Beauregard recognized the need for additional troops and asked Richmond for help. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnson was commanding the Army of the Shenandoah (11,000 troops) in the Shenandoah Valley to oppose a force of 18,000 Union soldiers of the Army of the Shenandoah commanded by General Robert Patterson. While this Union force occupied the northern parts of the Shenandoah Valley, General Patterson received orders to advance on the smaller Confederate force commanded by Johnson, and keep them from joining General Beauregard at Manassas.

General Johnson was ordered to move his brigades to Manassas to support General Beauregard’s Army. Moving his force toward Winchester, General Johnson was able to outmaneuver Union forces after the Battle of Hoke’s Run (Berkeley County, West Virginia) and load his troops on trains for transport to Manassas Junction. The failure of General Patterson to block General Johnson and keep him from arriving on the Manassas Battlefield in time to join the fight against General McDowell at Bull Run was the difference in victory versus defeat for the Union.

The Second Battle of Manassas occurred after the Union Army of the Potomac under the command of Major General George B. McClellan withdrew from the Peninsula Campaign after the Battle of Seven Pines near Richmond. Major General John Pope was given command of the Army of Virginia and consolidated his three separate corps (40,000 troops) at Culpeper on July 13, 1862 with the goal of capturing Gordonsville and the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

Concerned that his harvest supply line from the Shenandoah Valley to Richmond would stave his Army, General Lee sent Stonewall Jackson, and later General A. P. Hill to protect the rails from seizure by Pope’s troops moving south from Culpeper. After Jackson learned Pope’s Union Cavalry was observed probing his lines he pressed an attack on August 9th at the Battle of Cedar Mountain (8 miles south of Culpeper). The Confederate divisions of Jackson and Ewell defeated Pope and caused the Union Army of Virginia to retreat north of the Rappahannock River.

Confederate Cavalry Commander J.E.B. Stuart then flanked Pope’s Army and captured hundreds of soldiers, horses, and General Pope’s dispatch book. After General Lee learned of the contents of Pope’s dispatch book, he realized Pope possessed a superior force. General Lee changed his attack plan. Lee ordered the Stonewall Division (23,000 troops) to flank (right) Pope’s Army while Longstreet’s Corps kept the Federals in a defensive position along the Rappahannock River.

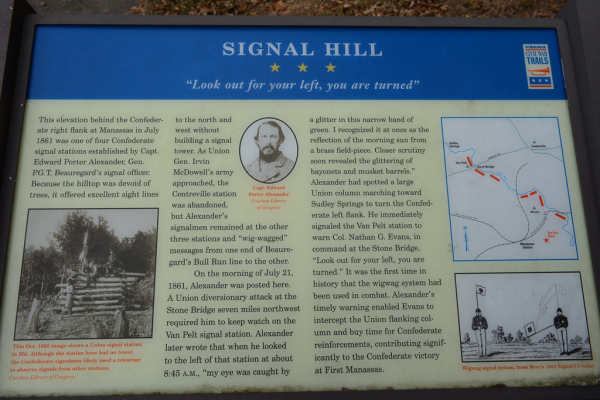

This Virginia Civil War Trails marker titled ‘Signal Hill’ is on Signal View Drive across from Signal Hill Park in Manassas. The marker reads:

“This elevation behind the Confederate right flank at Manassas in July 1861 was one of four Confederate signal stations established by Captain Edward Porter Alexander, General P. G. T. Beauregard’s signal officer. Because the hilltop was devoid of trees, it offered excellent sight lines to the north and west without building a signal tower. As Union General Irvin McDowell’s army approached, the Centreville station was abandoned, but Alexander’s signalmen remained at the other three stations and “wig-wagged” messages from one end of Beauregard’s Bull Run line to the other.

On the morning of July 21, 1861, Alexander was posted here. A Union diversionary attack at the Stone Bridge seven miles northwest required him to keep watch on the Van Pelt signal station. Alexander later wrote that when he looked to the left of that station at about 8:45 a.m., “my eye was caught by a glitter in this narrow band of green. I recognized it at once as the reflection of the morning sun from a brass field-piece. Closer scrutiny revealed the glittering of bayonets and musket barrels.” Alexander had spotted a large Union column marching toward Sudley Springs to turn the Confederate left flank. He immediately signaled the Van Pelt station to warn Colonel Nathan G. Evans, in command of the Stone Bridge, “Look out for your left, you are turned.” It was the first time in history that the wigwag system had been used in combat. Alexander’s timely warning enabled Evans to intercept the Union flanking column and buy time for Confederate reinforcements, contributing significantly to the Confederate victory at First Manassas.”

The actual location of the Confederate signal station is at the present day intersection of Signal Hill Road & Blooms Road. Behind this marker was a ridge line which a prepared Confederate trench led to a prepared defensive position near the intersection of Liberia Avenue and Quarry Road.

On August 24th Stonewall Jackson was ordered to destroy a section of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad to deny a supply line to the Union Army of Virginia. On August 27th Jackson arrived at Manassas Junction to find over a mile of Union supply trains full of food, ammunition, military clothing, first aid materials, equestrian feed & supplies, and hundreds of barrels of whiskey, brandy, & wine which General Jackson ordered destroyed. Jackson’s troops carried off as much as they could from the Union supply depot and burned the remaining supplies.

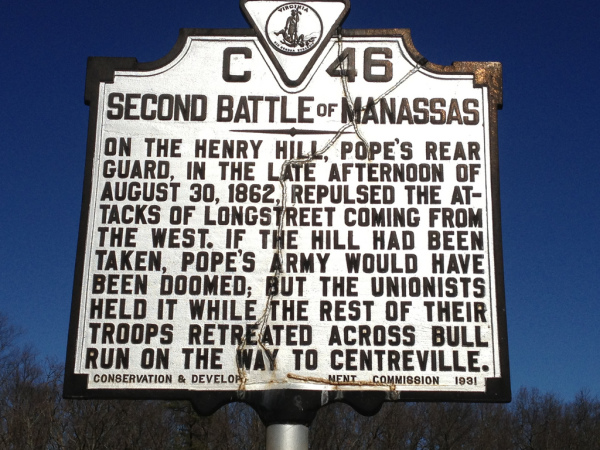

This Virginia Conservation & Development Commission historical marker (C-46 dated 1931) is on Lee Highway (Route 29) between Sudley Road and Bull Run (Stone Bridge). It is titled: ‘SECOND BATTLE of MANASSAS’. It reads:

“On the Henry Hill, Pope’s rear guard, in the late afternoon of August 30, 1862, repulsed the attacks of Longstreet coming from the west. If the hill had been taken, Pope’s army would have been doomed; but the unionists held it while the rest of their troops retreated across Bull Run on the way to Centreville.”

When General Pope learned of the raid of the supply train he believed Jackson’s force could not be reinforced and he was determined to find Jackson and attack the divided Confederate Army. Jackson’s force marched from Manassas Junction to Groveton (next to the battlefield of First Manassas) and used an unfinished railroad cut as a defensive position until he could be reinforced by Longstreet and Lee. On August 28th Jackson attacked a column of General John Gibbons Brigade marching on the Warrenton Turnpike, and the Battle of Second Manassas had begun. Jackson’s actions were planned to draw Pope into committing the bulk of his Army into battle knowing the arrival of Longstreet’s Corps would lead to a decisive victory.

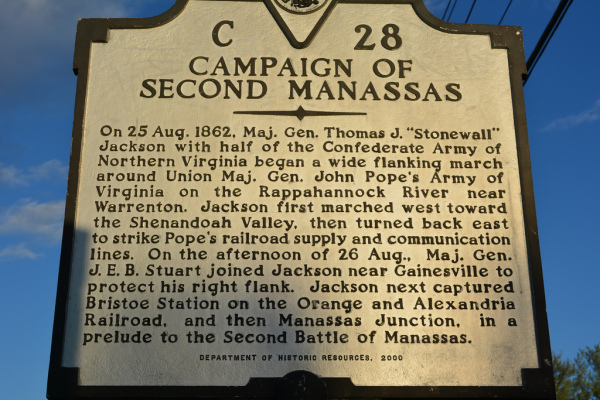

This 2000 Virginia Department of Historic Resources historical highway marker C-28 is on Lee Highway (Route 29) in Gainesville. The marker reads:

“On 25 August 1862, Major General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson with half of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began a wide flanking march around Union Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia on the Rappahannock River near Warrenton. Jackson first marched west toward the Shenandoah Valley, then turned back east to strike Pope’s railroad supply and communication lines. On the afternoon of 26 August, Major General J. E. B. Stuart joined Jackson near Gainesville to protect his right flank. Jackson next captured Bristoe Station on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, and then Manassas Junction, in a prelude to the Second Battle of Manassas.”

On Aug 29th General Pope was convinced he had trapped Jackson’s troops who were now stretched for 3,000 yards between Groveton on the Warrenton Turnpike to Sudley Springs on Bull Run. Pope launched a series of uncoordinated attacks against the trenched Confederates. There were several temporary penetrations of the Confederate positions but poor coordination, confusing orders, and battlefield execution by General Pope allowed Jackson’s men to beat back these attacks with heavy casualties on both sides.

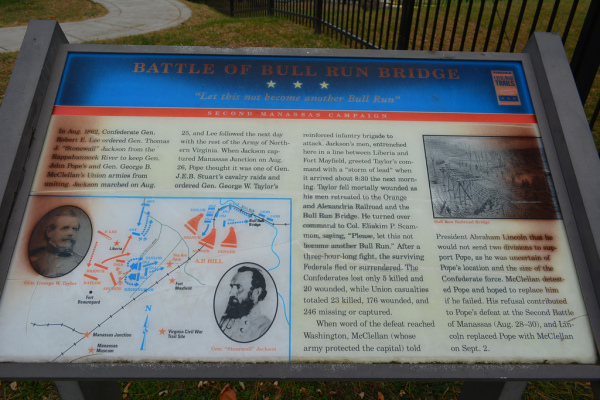

This Virginia Civil War Trails Second Manassas Campaign historical marker titled “Battle of Bull Run Bridge: Let this not become another Bull Run” is at the Conner House 8220 Conner Drive Manassas Park, Virginia 20111. The Marker reads:

“In August 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee ordered General Thomas J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson from the Rappahannock River to keep General John Pope’s and General George B. McClellan’s Union armies from uniting. Jackson marched on August 25, and Lee followed the next day with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. When Jackson captured Manassas Junction on August 26, Pope thought it was one of General J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry raids and ordered General George W. Taylor’s reinforced infantry brigade “First New Jersey Brigade” of 1st Division of VI Corps to attack. Jackson’s men, entrenched here in a line between Liberia and Fort Mayfield, greeted Taylor’s command with a “storm of lead” when it arrived about 8:30 the next morning. Taylor fell mortally wounded as his men retreated to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and the Bull Run Bridge. He turned over command to Colonel Eliakim P. Scamon, saying, “Please, let not this become another Bull Run.” After a three-hour-long fight, the surviving Federals fled or surrendered. The Confederates lost only 5 killed and 20 wounded, while Union casualties totaled 23 killed, 176 wounded, and 246 missing or captured.

When word of the defeat reached Washington, McClellan (whose army protected the capital) told President Abraham Lincoln that he would not send two divisions to support Pope, as he was uncertain of Pope’s location and the size of the Confederate force. McClellan detested Pope and hoped to replace him if he failed. His refusal contributed to Pope’s defeat at the Second Battle of Manassas (August 28-30), and Lincoln replaced Pope with McClellan on September 2.”

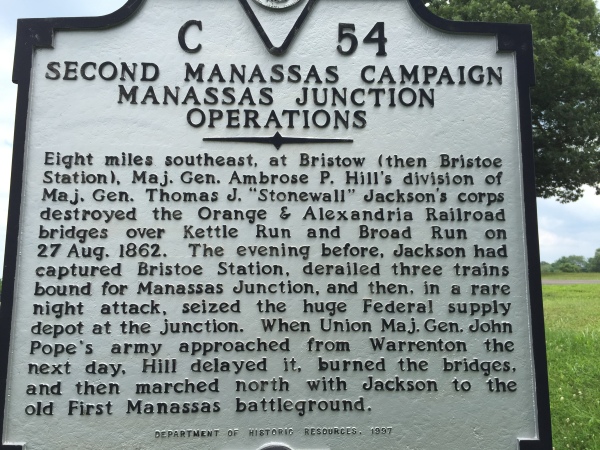

This 1997 Virginia Department of Historic Resources highway marker is near Warrenton, Virginia in Fauquier County. It is at the intersection of Lee Highway/Alexandria Turnpike (U. S. Route 15/29) and Broad Run Church Road (Route 600). The marker reads:

“Eight miles southeast, at Bristoe (then Bristoe Station), Major General Ambrose P. Hill’s division of Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps destroyed the Orange & Alexandria Railroad bridges over Kettle Run and Broad Run on 27 Aug. 1862. The evening before, Jackson had captured Bristoe Station, derailed three trains bound for Manassas Junction, and then, in a rare night attack, seized the huge Federal supply depot at the junction. When Union Major General John Pope’s army approached from Warrenton the next day, Hill delayed it, burned the bridges, and then marched north with Jackson to the old First Manassas battleground.

On August 29th at 8:15 a. m. Union Cavalry Commander General John Buford reported to General McDowell (supporting the Army of Virginia after the Peninsula Campaign) of Longstreet’s 25,000 troops arriving at Gainesville. McDowell held the information until 7:00 p. m. McDowell also refused to move two full and ready corps of the Army of the Potomac from Alexandria to Manassas to support Pope during Second Manassas. His lack of cooperation was a political tactic to have General Pope removed from command, and reinstated to control all Union armies. His actions were later proven to be a court-martial offense although it was never addressed as such by President Lincoln.

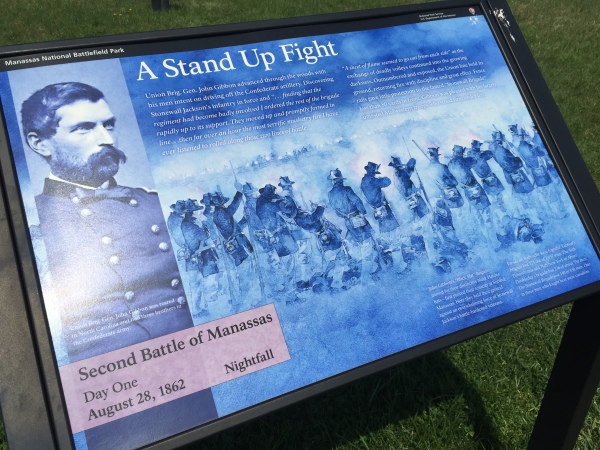

Second Battle of Manassas

Day One

August 28, 1862 Nightfall

Union Brigadier General John Gibbon advanced through the woods with his men intent on driving off the Confederate artillery. Discovering Stonewall Jackson’s infantry in force and “…finding that the regiment had become badly involved I ordered the rest of the brigade rapidly up to its support. They moved up and promptly formed in line…then for over an hour the most terrific musketry fire I have ever listened to rolled along those two lines of battle.”

A sheet of flame seemed to go out from each side” as the exchange of deadly volleys continued into the growing darkness. Outnumbered and exposed, the Union line held its ground, returning fire with discipline and great effect. Fence rails gave little protection to the famed “Stonewall Brigade” less than 80 yards in front. Gibbon was pleased with his largely untested Midwestern troops who stood firm under fire.

Caption (lower left):

Union Brigadier General John Gibbon was reared in North Carolina and had three brothers in the Confederate Army.

Caption (bottom right):

John Gibbon’s “Blackhat” Brigade-named for their distinctive black Hardee hats-first proved their tenacity at Second Manassas. Here they held their ground against an overwhelming force of Stonewall Jackson’s battle-hardened veterans.

This National Park Service interpretive marker reads:

“My command was advanced…until it reached a commanding position near Brawner’s house. By this time it was sunset; but as [the Union] column appeared to be moving by, with its flank exposed, I determined to attack at once.”

– Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson, 1862

The sketch shown in this interpretive marker shows the battlefield positions of the 19th Indiana Infantry Regiment and Battery B, 4th U. S. Artillery.

Observing a column of tired, unsuspecting Federal troops marching eastward on the Warrenton Pike (U.S. Route 29 today), General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson chose to reveal his position and draw the Union Army of Virginia into battle on ground favoring the Confederates. The Federals raced for cover along the roadside as Confederate shells burst overhead. The Battle of Second Manassas had begun.

Two divisions of Jackson’s hardened infantry swarmed from the wooded ridge behind the house but met unexpected stiff resistance from six Union regiments that advanced from the turnpike. Confederate division commanders William Taliaferro and Richard Ewell were severely wounded in the intense, close range firefight that continued until darkness fell. The fight at Brawner’s Farm ended in stalemate leaving Jackson frustrated by his troops’ inability to break the Union line.

This National Park Service interpretive marker is just west of the Brawner Farm House next to a line of Confederate artillery pieces at Manassas National Battlefield Park.

Second Battle of Manassas

Day Three

August 30, 1862 3 p. m.

On the morning of August 30, 1862, Confederate Col. Stephen D. Lee deployed 18 guns from his artillery battalion along this commanding ridge. Additional cannon, under Major Lindsey M. Shumaker, unlimbered to his left. The artillery linked the two wings of the Confederate army. In total, as many as 36 guns occupied this ground overlooking the rolling fields of Lucinda Dogan’s farm.

At 3:00 p.m., Union troops poured out of the Groveton woods to attack Jackson’s line along the unfinished railroad. From this position, Confederate gunners had a clear view of the assault – the most formidable onslaught of the three days. The artillery concentrated their fire on the advancing enemy line, one-half mile ahead. The lethal bombardment kept reinforcements from crossing the field and helped ensure the failure of the Union attack.

“Our position was an admirable one and the guns were well served.”

-Colonel Stephen D. Lee.

After General Pope realized Longstreet’s Corps was on the battlefield he mistakenly believed the arrival of Longstreet was to provide support to Jackson for a withdrawal of the Confederate Army. Instead, Longstreet reinforced and extended Jackson’s Line across the Warrenton Turnpike past Chinn Ridge to Bald Hill. On August 30th Pope mistakenly interpreted enemy movement as a retreat and ordered an attack. Confederate artillery repulsed the Federal attack, and Lee and Longstreet took advantage of disorganized enemy forces after the failed attack by launching a massive counterattack on the Union left. After initial success Pope’s Army was able to neutralize the attack at Chinn Ridge long enough for Pope to consolidate his forces on Henry Hill where a rear guard was formed, and the Army of Virginia could retreat from the battlefield in an orderly fashion.

– Dwayne Moyers

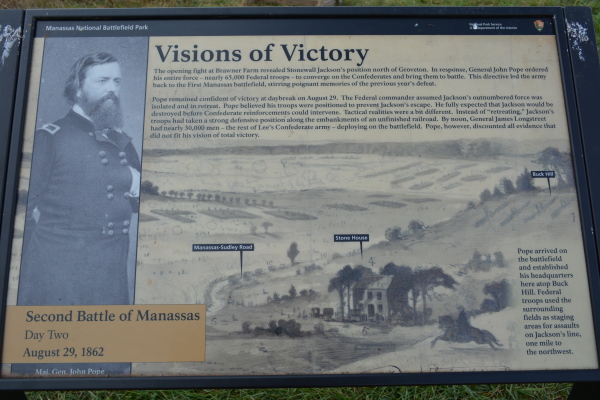

This National Park Service interpretive marker titled ‘Visions of Victory’ is on top of Buck Hill (sleigh riding hill directly behind Stone House) at Manassas National Battlefield Park. The marker reads:

“The opening fight at Brawner Farm revealed Stonewall Jackson’s position north of Groveton. In response, General John Pope ordered his entire force – nearly 65,000 Federal troops – to converge on the Confederates and bring them to battle. This directive led the army back to the First Manassas battlefield, stirring poignant memories of the previous year’s defeat.

Pope remained confident of victory at daybreak on August 29. The Federal commander assumed Jackson’s outnumbered force was isolated and in retreat. Pope believed his troops were positioned to prevent Jackson’s escape. He fully expected that Jackson would be destroyed before Confederate reinforcements could intervene. Tactical realities were a bit different. Instead of “retreating.” Jackson’s troops had taken a strong defensive position along the embankments of an unfinished railroad. By noon, General James Longstreet had nearly 30,000 men – the rest of Lee’s Confederate army – deploying on the battlefield. Pope, however, discounted all evidence that did not fit his vision of total victory.”

Caption:

Pope arrived on the battlefield and established his headquarters here atop Buck Hill. Federal troops used the surrounding fields as staging areas for assaults on Jackson’s line, one mile to the northwest.

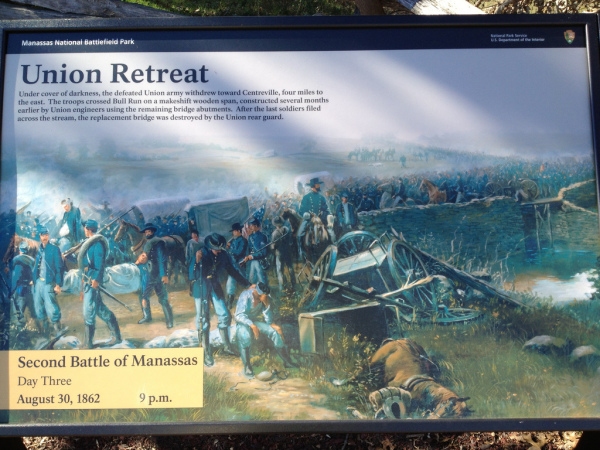

This National Park Service interpretive marker titled ‘Union Retreat’ is at Stone Bridge next to Bull Run on Lee Highway (Route 29) in Fairfax County. The marker reads:

“Second Battle of Manassas

Day Three

August 30, 1862 9 p.m.

Under cover of darkness, the defeated Union army withdrew toward Centreville, four miles to the east. The troops crossed Bull Run on a makeshift wooden span, constructed several months earlier by Union engineers using the remaining bridge abutments. After the last soldiers filed across the stream, the replacement bridge was destroyed by the Union rear guard.”

The Union attack on July 21, 1861 at Sudley Springs was originally planned to cross Bull Run at the Stone Bridge. But false rumors lead Union planners to believe the Stone Bridge was readied with explosives for the Union approach. As a result, the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, the nucleus of the Army of Potomac, moved north to cross Bull Run and attacked the Confederate Army of the Potomac under the command of General P. T. Beauregard. The Union attack swept south across the Warrenton Turnpike and pressed forward to Henry Hill. There the Union attack ran into Virginia’s First Brigade (later known as the Stonewall Brigade). General Thomas Jonathan Jackson stood tall on Henry Hill and with the help of the Third Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah under General Barnard Elliot Bee of South Carolina, the Union assault turned into a retreat. The Union Army fled east using the Stone Bridge to cross Bull Run and use the Warrenton Turnpike to flee to Centreville, consolidate, and return to Washington.

The original Stone Bridge (c. 1825) remained intact through 1861. On the 9th of March 1862 General Joseph E. Johnston and the Confederate Army of the Potomac left winter camp in Centreville and Manassas. After securing supplies at Manassas Junction, the army rear guard used explosives to destroy the Stone Bridge after anticipating a march south to defend Union advances on Richmond.

Union Army engineers eventually constructed a temporary wooden span across Bull Run using the remaining bridge abutments. This bridge served Union General John Pope’s army at Second Manassas, August 28-30, 1862. After suffering another costly defeat, Union forces used the Warrenton Turnpike bridge as their primary line of retreat. In the early hours of August 31, the bridge was again destroyed, this time by the Union rear guard.

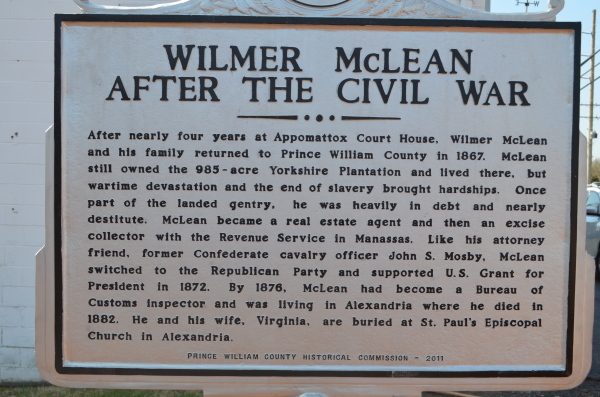

This 2011 Prince William County Historical Commission highway marker is near the the intersection of Centreville Road (Route 28) and Yorkshire Lane in Manassas, Virginia. The marker reads:

“After nearly four years at Appomattox Court House, Wilmer McLean and his family returned to Prince William County in 1867. McLean still owned the 985-acre Yorkshire Plantation and lived there, but wartime devastation and the end of slavery brought hardships. Once part of the landed gentry, he was heavily in debt and nearly destitute. McLean became a real estate agent and then an excise collector with the Revenue Service in Manassas. Like his attorney friend, former Confederate cavalry officer John S. Mosby, McLean switched to the Republican Party and supported U.S. Grant for President in 1872. By 1876, McLean had become a Bureau of Customs inspector and was living in Alexandria where he died in 1882. He and his wife, Virginia, are buried at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria.”

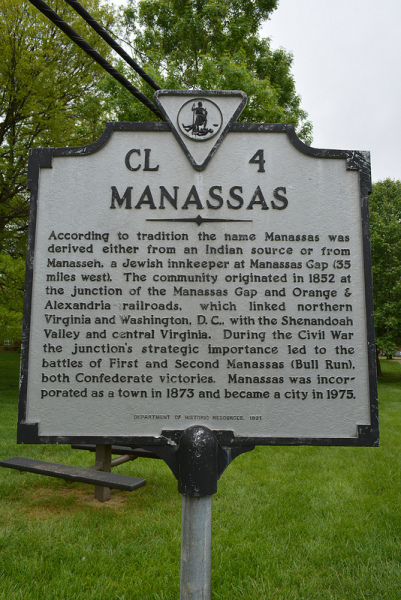

This 1991 Virginia Department of Historical Resources interpretive marker CL-4 titled, ‘MANASSAS’ is in Nelson Park near the intersection of Grant Avenue (Route 234) and Stuart Avenue in the City of Manassas.

The ‘Manassas’ marker reads:

“According to tradition the name Manassas was derived either from an Indian source or from Manasseh, a Jewish Innkeeper at Manassas Gap (35 miles west). The community originated in 1852 at the junction of the Manassas Gap and Orange & Alexandria railroads, which linked northern Virginia and Washington, D. C., with the Shenandoah Valley and central Virginia. During the Civil War the junction’s strategic importance led to the battles of First and Second Manassas (Bull Run), both Confederate victories. Manassas was incorporated as a town in 1873 and became a city in 1975.”

Manassas Area Picture Albums

- Bristow, Gainesville, Haymarket Aden, Brentsville, Bristow Station Battlefield Heritage Park, historical highway markers, Nokesville, Prince William County interpretive markers, residential subdivisions, and Virginia Civil War Trails interpretive markers.

- Manassas National Battlefield Park Blackburn’s Ford, Brawner Farm, Buck Hill, Chinn Ridge, Conner House, Groveton Cemetery, Hazel Plain, Henry Hill, Hillwood Mansion, Matthews Hill, Signal Hill, Stone House, Sudley Springs, Thornberry House

- Manassas, Virginia Residential subdivisions, historical markers, government buildings, retail stores, historic buildings, and church buildings, George Mason University Science and Technology Campus, historical makers of the Manassas Industrial School (Jennie Dean Memorial), City of Manassas historic district, Manassas National Battlefield Park, and Prince William County.